RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 17 Issue No: 4 pISSN:

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Seema Shantilal Pendharkar, MDS (Oral and Maxillofacial surgery) Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, Maharashtra, India.

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Seema Shantilal Pendharkar, MDS (Oral and Maxillofacial surgery) Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, Maharashtra, India., Email: dr.seemapendharkar@gmail.com

Abstract

Disorders affecting the hard and soft tissues of the face, including the dental arches, are categorized as oral and maxillofacial disorders. The use of bioactive nanomaterials (NMs) in medicine has advanced significantly, with nanotechnology contributing notable advances in both prevention and therapy. This review highlights current advancements in nanotechnology for managing diseases of the mouth, jaw, and soft palate, with an emphasis on improving the standard of oral and maxillofacial care. Nanoscale materials beneficial for oral health include polymers, liposomes, particles, micelles, capsules, and scaffolds. By simulating the formation of natural tissue, they improve the restoration of tissue function, facilitate identification and treatment of disorders, and aid in the repair of damaged tissues. Research demonstrates that applying nanotechnology to reconstructive surgery is a promising field that is still in its infancy, and if this developing technology is to eventually replace present surgical practices, considerable research is needed. Nevertheless, as understanding of nanotechnology expands, interest and advancement in this discipline are expected to continue.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Disorders affecting the soft and hard tissues of the face, jaw, and dental arches are included in oral and maxillofacial ailments.1,2 These disorders are commonly caused by chemical, physical, and microbiological factors that coexist with systemic illnesses.3 In these circumstances, the oral infectious diseases such as periodontitis and caries, as well as deficiencies in craniofacial tissue brought on by trauma, cysts, and abnormalities become evident.

In addition, diseases pertaining to the central nervous system, salivary glands, and disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) are typically detected.4 The employment of a variety of biosafe materials is crucial in this situation to enhance clinical benefits and promote tissue healing. For instance, autogenous bone grafts, due to their exceptional biocompatibility, are regarded as the primary treatment method for facilitating maxillofacial bone replacement.5,6

The growing number of papers in the field indicates a considerable rise in research on the applications of nanotechnology in the medical profession over the past ten years. In particular, reconstructive surgery is a rapidly developing area of biotechnology that combines the study of cell biology, material science, and bioengineering with the goal of effectively replacing or repairing tissue. Reconstructive surgery, in its widest definition, refers to procedures that return an affected body component to its original anatomical or functional state. This paper examines the various applications of nanotechnology in reconstructive surgery, along with its general characteristics. It also analyzes the domains in which nanotechnology is applied in research settings, with the aim of improving outcomes and advancing its use in clinical practice.

Nanomaterials (NMs)

NMs are typically divided into several categories, such as metal oxide NPs, metal NPs, carbon-based NMs, polymeric NMs, and quantum dots.7 Both natural and man-made sources contribute to the presence of NMs in the environment, originating either accidentally or through nanotechnological processes.8 Natural carbon-based NMs arise from combustion and other high-energy events, such as lightning, volcanic eruptions, sandstorms, and wildfires. It has been observed that combustion, which is concealed by mining and friction processes, is the primary source of carbon-based NMs when anthropogenic sources are taken into account. This course is being monitored by nanotechnology, which creates NMs on purpose. In fact, several carbon allotropes and amorphous carbon NPs are present in the carbon-based NMs.9 They have the unique characteristics of sp2- and sp3-hybridized carbon bonds, together with non-size physiognomies in their chemistry and physics. The combinations in this group that have been studied the most are pristine fullerenes. In actuality, unsaturated, unfunctionalized carbon molecules with at least 20 carbon atoms arranged in a hollow polyhedron constitute virgin fullerenes.10

The nanoscale materials, or NMs, are manufactured components with extremely small dimensions that exhibit unique chemical and physical properties.11 Their properties differ markedly from those of their bulk components due to the specific dimensions. As a result, the behaviour of NMs can be unpredictable, in some cases, remains incompletely understood. For example, evidence suggests that NMs can penetrate blood-brain barriers (BB) and skin to effect host cells in an undesired way.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that NMs can be reformulated and used as novel compounds in accordance with standard principles. NMs are already present in a variety of food additives and consumer products; however, their presence has traditionally not been disclosed nor have their potential effects on human health or the environment been clearly demonstrated.13

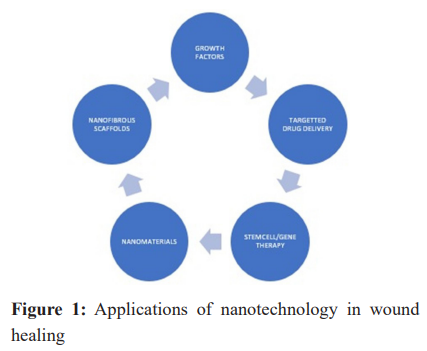

Therapeutic Applications of Nanotechnology in Maxillofacial Tissue Regeneration (Figure 1)

Nerve repair and regeneration

Restoring damaged nerves is particularly challenging since mature neurones are incapable of dividing. Minor nerve injuries are typically managed by suturing the severed ends, whereas significant nerve tissue loss may require an autologous nerve graft. However, this approach for severe injuries might result in painful neuromas and loss of function at donor locations. Consequently, its status as the optimal treatment remains debated.14,15

A recent study demonstrated the use of composite scaffolds for nerve regeneration in rats with lesions. The scaffolds, composed of electrospun microfibers of poly(Llactide-coglycolide) (PLGA) and poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL), served as guide tubes. These biodegradable polymers can be spun into flexible scaffolds using the electrospinning technique. Using this scaffold, an in vivo sciatic nerve gap of 10 mm was regenerated. Rats with sciatic nerve lesions served as the control group, while rats in the experimental group received tubular scaffolds inserted at the severed nerve terminals. Four months following the procedure, the control group showed no reattachment of the sciatic nerve stumps. In contrast, the tubular scaffolds facilitated reconnection of the sciatic nerve terminals and regeneration of neural tissue in most treated rats. Evidence of myelination, collagen IV deposition, and neuronal markers of target muscle re-establishment and re-innervation was also observed. No discernible inflammatory response was seen in the majority of treated rats. The lag in nerve conduction was the reason for this unsatisfactory functional recovery. However, the study's findings are encouraWging in terms of promoting and guiding rejuvenation of peripheral nerve function.16

Soft tissue regeneration

One study evaluated a novel cell-seeding technique that permits a predetermined number of cells to disperse across a nanofiber scaffold. Rats received one of four implant types: acellular pig dermis (ENDURAGen), acellular human cadaveric dermis (AlloDerm), or a polycaprolactone (PCL)/collagen nanofiber scaffold seeded with primary fibroblasts. Postoperatively, the rats were given buprenorphine and enrofloxacin in their drinking water for four days as a preventative measure, and were closely monitored. Even if host cells replace the seeded cells, this cell seeding technique appears to reduce inflammation and boost acceptance. This provides credence to the view that transient cell presence on the scaffold - sufficient to allow proliferation and production of extracellular matrix proteins, may be less crucial for integration into host tissue than cell collection.17 The multilayer structures have the ability to be folded before implanting, enabling the physician to schedule the implant at the same time as the surgery. This study showed that multilayer PCL/collagen nanofiber constructs can be seeded with cells, which enhances vascularization. A large number of donor-derived cells were found near the nanofiber surface of individual layers. The cells that were employed to differentiate between the donor and host cells expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein.

Implants seeded with cells resulted in significantly greater neovascularization. This might be useful for dermal augmentation or replacement. The cell-seeded constructs could serve as a model for further research on engineered constructs.18

Hard tissue regeneration

Carbon nanotubes, a type of nanomaterial, are gaining popularity and are recommended as a successful treatment option for bone regeneration. Their beneficial effects are primarily attributed to their mechanical, electrical, and biocompatibility properties. Published research indicates that a combination of graphene and single-walled carbon nanotubes (G/SWCNT) can enhance the production of osteoblasts from primary stem cells. Furthermore, by activating the p38 signalling pathway and downregulating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 axis, this combination effectively suppresses adipogenesis.19 Additionally, a sandwich-like scaffold consisting of a nano-calcium sulfate disc and a platelet-rich plasma (PRP) fibrin gel containing stem cells overexpressing bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) can promote bone healing in animal models with calvarial anomalies.20 A 3D printed poly (lacticcoglycolic acid)/β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) scaffold, chitosan/polyethylene oxide (CTS/PEO) scaffold, and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) scaffold are examples of similar scaffolds that have been shown to promote bone regeneration in vivo. 21 These results make them a promising treatment approach for repairing bone abnormalities. Similarly, other studies have demonstrated the potential to create ultralight 3D hybrid nanofiber aerogels, such as electrospun PLGA-collagen-gelatin containing heptaglutamate E7 domain-specific BMP-2 peptides, to effectively treat cranial bone injuries.22 In animal models, this intervention led to increased bone volume and bone formation area, as shown by histopathological investigation.22 Additionally, rat maxillae with critical-sized alveolar bone deficiencies were injected with alendronate based nanofiber (ALN).23 This intervention significantly enhanced the production of new bone in the injection site, according to the observation. These findings indicate that mineralized nanofiber sections effectively promote bone regeneration.23

Cartilage tissue regeneration

The primary goal of NMs in this context is to serve as a substitute by increasing the surface area, enhancing porosity, and mimicking the extracellular milieu. Cartilage regeneration in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), auricular region, and nasal structures is an integral part of oral and cranio-maxillofacial cartilage reconstruction.24,25 Nanofibers are frequently used to repair cartilage abnormalities and have shown notable therapeutic effects in vivo. PCL fibrous scaffolds, PCL poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-PCL scaffolds, and a novel biomimetic and bioactive electrospun cartilage loaded with continuous growth factor transport microspheres are examples of functional nanofibers that are currently known.26 Cartilage regeneration also employs a class of materials known as graphene oxide (GO), primarily because of its high surface area, mechanical strength, and electrical/chemical modification capabilities.27 For instance, specialists have developed a hybrid scaffold composed of GO, PEG methyl ether-ε-caprolactone-acryloyl chloride, and methacrylated chondroitin sulfate to enhance cartilage regeneration in rabbits with abnormalities.28 This scaffold provides optimal porosity, pore size, conductivity, and compression modulus, just like the normal cartilage extracellular matrix. The nasal and auricular cartilages play a major role in maintaining the exterior activity.29 Unlike the TMJ's articular cartilage, they have distinct forms and functions, which creates intricate requirements for the application of biomaterials in cartilage tissue regeneration.

Conclusion

In dental therapy, nanotechnology has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its remarkable achievements. Undoubtedly, NMs have vast potential in the regrowth of cranio-maxillofacial bone and teeth, the management of oral disorders, especially in the prevention of caries, the osseointegration of dental implants, and the production of prosthodontic materials. However, the potential benefits must always be balanced against possible negative effects. The application of nanotechnology-based dental appliances has drawbacks that should be considered before release to the market. This is because the oral cavity is a unique microenvironment where “targeted” and “non-targeted” organs interact. Factors such as pH and plaque biofilm, combined with the saliva's buffer system, typically regulate how effectively these NMs function in the oral cavity. Furthermore, these nanofillings tend to wear down due to erosion, dissolution, and bite forces, which can cause disruption to the gingiva, mucosa, and tooth surface. In addition, NMs produced in the oral cavity may be ingested and pass through the digestive system, resulting in systemic adverse effects. It is evident that nanotechnology offers a wide range of applications in reconstructive surgery, and this field will continue to expand. In particular, soft tissue reconstruction, collagen implants, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and nerve regeneration and repair have all benefited from the use of nanotechnology. It is currently difficult to find follow-up studies on recent research, making it challenging to determine the reproducibility of earlier findings. Research on nanotechnology in relation to bone prosthetics is already underway, and as our understanding of nanoparticles advances, new applications are likely to emerge that will further enhance reconstructive surgery. Although this review does not encompass every application in this rapidly expanding sector, it provides valuable insights from the available evidence.

Conflict of interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

- Hariri F, Chin SY, Rengarajoo J, et al. Distraction osteogenesis in oral and craniomaxillofacial reconstructive surgery [Internet]. Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. IntechOpen; 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.81055

- Kouhbanani MAJ, Sadeghipour Y, Sarani M, et al. The inhibitory role of synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against Hep-G2, MCF-7, and HT-29 cell lines: The inhibitory role of NiO NPs against Hep-G2, MCF-7, and HT-29 cell lines. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews 2021;14(3):444-54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253. 2021.1939435

- Meglioli M, Naveau A, Macaluso GM, et al. 3D printed bone models in oral and cranio-maxillofacial surgery: a systematic review. 3D Print Med 2020;6(1):30. Available from: https:// doi.org/10.1186/s41205-020-00082-5

- Balon P, Vesnaver A, Kansky A, et al. Treatment of end stage temporomandibular joint disorder using a temporomandibular joint total prosthesis: The Slovenian experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2019;47(1):60-5. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jcms.2018.10.022

- Sanz M, Dahlin C, Apatzidou D, et al. Biomaterials and regenerative technologies used in bone regeneration in the craniomaxillofacial region: Consensus report of group 2 of the 15th European Workshop on Periodontology on Bone Regeneration. J Clin Periodontol 2019;46(Suppl21):82-91. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13123

- Nasirmoghadas P, Mousakhani A, Behzad F, et al. Nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapies: an innovative strategy. Biotechnol Prog 2021;37(2):e3070. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.3070

- Peng G, Sharshir SW, Wang Y, et al. Potential and challenges of improving solar still by micro/ nanoparticles and porous materials-A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021;311:127432. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127432

- Bognár S, Putnik P, Šojić Merkulov D. Sustainable green nanotechnologies for innovative purifcations of water: Synthesis of the nanoparticles from renewable sources. Nanomaterials 2022;12(2):263. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12020263

- Adeel M, Farooq T, White JC, et al. Carbon-based nanomaterials suppress tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) infection and induce resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. J Hazard Mater 2021;404:124167. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124167

- Afsharpanah F, Cheraghian G, Akbarzadeh Hamedani F, et al. Utilization of carbon-based nanomaterials and plate-fin networks in a cold PCM container with application in air conditioning of buildings. Nanomaterials 2022;12(11):1927. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12111927

- Bréchignac C, Houdy P, Lahmani M. Nanomaterials and nanochemistry. Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3- 540-72993-8

- Dugershaw BB, Aengenheister L, Hansen SSK, et al. Recent insights on indirect mechanisms in developmental toxicity of nanomaterials. Part Fibre Toxicol 2020;17(1):31. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1186/s12989-020-00359-x

- Kermanizadeh A, Balharry D, Wallin H, et al. Nanomaterial translocation-the biokinetics, tissue accumulation, toxicity and fate of materials in secondary organs-a review. Crit Rev Toxicol 2015;45(10):837-72. Available from: https://doi.or g/10.3109/10408444.2015.1058747

- Heath CA, Rutkowski GE. The development of bioartificial nerve grafts for peripheral regeneration. Trends Biotechnol 1998;16:163-168. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167- 7799(97)01165-7

- Wang S, Wan AC, Xu X, et al. A new nerve guide conduit material composed of a biodegradable poly(phosphoester). Biomaterials 2001;22:1157- 1169. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0142-9612(00)00356-2

- Panseri S, Cunha C. Electrospun micro- and nanofiber tubes for functional nervous regeneration in sciatic nerve transections. BMC Biotechnol 2008;8:39. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472- 6750-8-39

- Ghaati S, Unger RE, Webber MJ, et al. Scaffold vascularisation in vivo driven by primary human osteoblasts in concert with hot inflammatory cells. Biomaterials 2011;32:8150-8160. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.041

- Barker AD, Bowers BT, Hughley B, et al. Multilayer cell-seeded polymer nanofiber constructs for soft-Yan X, Yang W, Shao Z, et al. Graphene/single-walled carbon nanotube hybrids promoting osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by activating p38 signalling pathway. Int J Nanomedicine 2016;11:5473-5484. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S115468tissue reconstruction. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139:914-922. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4119

- Yan X, Yang W, Shao Z, et al. Graphene/single-walled carbon nanotube hybrids promoting osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by activating p38 signalling pathway. Int J Nanomedicine 2016;11:5473-5484. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S115468

- Liu Z, Yuan X, Fernandes G, et al. The combination of nano-calcium sulfate/platelet rich plasma gel scaffold with BMP2 gene-modified mesenchymal stem cells promotes bone regeneration in rat critical-sized calvarial defects. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8(1):122. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1186/s13287-017-0574-6

- Vella JB, Trombetta RP, Hofman MD, et al. Three dimensional printed calcium phosphate and poly (caprolactone) composites with improved mechanical properties and preserved microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res A 2018;106(3):663-72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.36270

- Weng L, Boda SK, Wang H, et al. Novel 3D hybrid nanofiber aerogels coupled with BMP‐2 peptides for cranial bone regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater 2018;7(10):e1701415. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1002/adhm.201701415

- Boda SK, Wang H, John JV, et al. Dual delivery of alendronate and E7-BMP-2 peptide via calcium chelation to mineralized nanofiber fragments for alveolar bone regeneration. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2020;6(4):2368-75. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00145

- Sandor G, Lindholm T, Clokie C. Bone regeneration of the cranio-maxillofacial and dento-alveolar skeletons in the framework of tissue engineering. Topics in Tissue Engineering 2003;7:1-46.

- Kuttenberger JJ, Hardt N. Long-term results following reconstruction of craniofacial defects with titanium micromesh systems. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2001;29(2):75-81. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1054/jcms.2001.0197

- Ogueri KS, Laurencin CT. Nanofiber technology for regenerative engineering. ACS Nano 2020;14(8):9347-63.Available from: https://doi. org/10.1021/acsnano.0c03981

- Alam SN, Sharma N, Kumar L. Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO) by modifed hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene 2017;6(1):1-18. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4236/graphene.2017.61001

- Liao J, Qu Y, Chu B, et al. Biodegradable CSMA/ PECA/graphene porous hybrid scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering. Sci Rep 2015;5:9879. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09879

- Ho TT, Cochran T, Sykes KJ, et al. Costal and auricular cartilage grafts for nasal reconstruction: An anatomic analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2017;126(10):706-11. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1177/0003489417727549