RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Department of Community Medicine, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2Department of Community Medicine, Palakkad Institute of Medical Sciences, Palakkad, Kerala, India

3Department of Community Medicine, BGS Medical College & Hospital, Adichunchanagiri University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4Dr. Ipsita Debata, Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences,Kushabhadra Campus, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India.

5Department of Community Medicine, AJ Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Kuntikana, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

6Department of Community Medicine, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Ipsita Debata, Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences,Kushabhadra Campus, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India., Email: drdebataipsita@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Geographic Information System (GIS) technology offers a promising approach for visualizing disease distribution patterns, thereby enhancing tuberculosis (TB) surveillance, resource allocation, and the planning of targeted interventions.

Aim: The objective of the study was to evaluate the usefulness of GIS in mapping the geospatial distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis cases within the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) area of Bengaluru and to analyze associated trends, clustering patterns, and demographic characteristics.

Methods: This cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out across all 198 BBMP wards. Data were obtained from the NIKSHAY portal for TB patients registered between January and June 2020. GIS mapping was performed using QGIS software based on the PIN codes of patients’ residences. Analyses included drug resistance patterns, treatment outcomes, demographic details, and the spatial distribution of TB cases.

Results: A total of 1,498 pulmonary tuberculosis cases were mapped. The mean age of patients was 38.4 years, and the majority (63%) were male. Spatial analysis identified clustering in specific wards, particularly wards 134, 136, 141, and 157. Around 73.2% of all TB cases were newly diagnosed. Drug resistance to isoniazid and/or rifampicin was the most common form of drug-resistant TB, detected in 115 patients (7.7%). A declining trend in case registrations was observed during the study period, likely due to COVID-19 pandemic related disruptions.

Conclusion: GIS is a useful tool for TB control, enabling the identification of drug-resistance clusters and high-burden areas. These spatial insights support strengthened surveillance, targeted public health interventions, and effective resource allocation contributing to improved efforts to contain TB.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health security threat, causing approximately 1.5 million deaths each year, continuing to be the world’s leading infectious killer. In 2021, an estimated 10.6 million people developed TB worldwide.1 Since the adoption of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) End TB Strategy and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the world has witnessed growing political commitment and efforts to end the TB epidemic.2 Multiple measures have been implemented for the effective global rollout of the End TB Strategy.

A geographic information system (GIS) is a computer-based platform for capturing, storing, checking, and displaying data related to locations on Earth’s surface. With the advancements in Information Technology, the scope of GIS has been redefined and expanded.3 Health GISs are integrated systems containing tools for managing, inquiring, analyzing, and presenting spatially-referenced health data. Mapping through GIS can significantly enhance the assessment of environmental health risks, enabling more effective analysis and understanding of the patterns and relationships in health-related data.

A geography-based screening and treatment approach that evaluates the clusters of TB cases and their characteristics can serve as an effective method for control of tuberculosis cases. In this study, we aimed to use GIS technology as a tool to identify the geospatial distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis cases in a metropolitan city.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining administrative approval from the District Tuberculosis Officer and ethical approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee, this cross-sectional illustrative study was conducted across the 198 wards of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahangara Palike (BBMP), the administrative jurisdiction of Bengaluru. The study population was identified using data from the NIKSHAY portal. Details of tuberculosis patients registered between January 2020 and June 2020 were included. The pin code of each patient’s address was used to locate the corresponding geo-coordinates. The study area comprised pin codes ranging from 560001 to 560098, and the patients residing outside the BBMP limits were excluded. In total, data from 1498 pulmonary tuberculosis patients were included in the study.

Statistical Analysis

The study area map was created, and the list of wards was obtained from the municipal authority. Spatial heterogeneity of pulmonary tuberculosis cases was examined using QGIS software. The results were expressed as numbers and percentages, and displayed through graphs, figures, and tables.

Results

From January to June 2020, a total of 1498 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis were identified and enrolled in the study from the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike. The spatial distribution of cases was determined using the pin code of each patient’s residential address.

Distribution Based on Age Group

The study included 1,498 participants, comprising 948 (63.3%) males and 550 (36.7%) females. The mean age of the study population was 38.38 ± 15.964 years. The largest age group was 15-25 years, accounting for 23.1% (346) of the total population, with 14.5% (137) of males and 38.0% (209) of females. This was followed by the 26-35 years age group, comprising 21.2% (317) of participants-21.5% (204) males and 20.5% (113) females. The 46–55 years group constituted 20.5% (307) overall, including 23.6% (224) of males and 15.1% (83) of females. Participants aged 36-45 years represented 18.4% (276), with 21.5% (204) males and 13.1% (72) females. The 56-65 years age group accounted for 9.0% (135), including 11.2% (106) of males and 5.3% (29) of females. The elderly group aged over 65 years comprised 5.0% (75), with 5.9% (56) males and 3.5% (19) females. The youngest age group, 0-14 years, accounted for 2.8% (42) of the total population, with 1.8% (17) males and 4.5% (25) females.

Spatial Distribution, Trend of Tuberculosis Case Registration, and Clustering of Cases

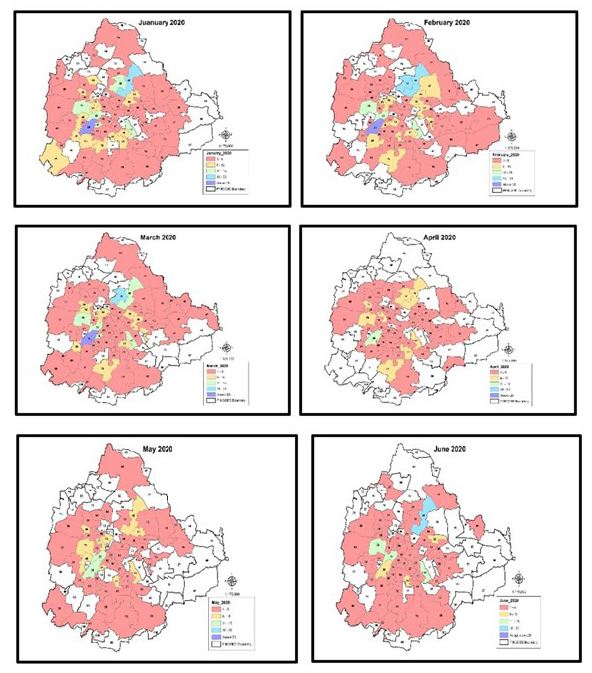

The pattern of distribution of tuberculosis cases based on the month of diagnosis is illustrated in Figure 1. The maximum number of cases was reported in January 2020. A sharp decline was noted during the COVID-19 lockdown in March and April 2020. Case reporting gradually increased again in May and June. Several wards exhibited persistent hotspots, suggesting the presence of vulnerable populations or localized transmission.

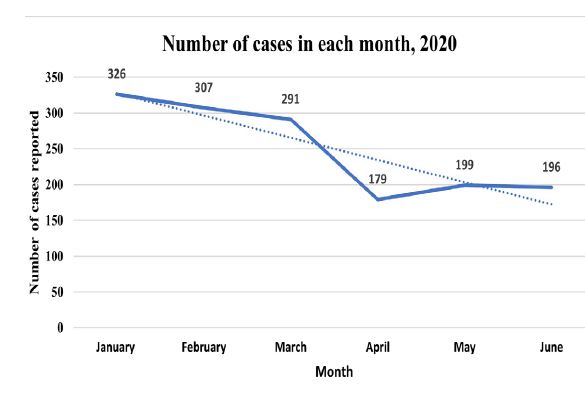

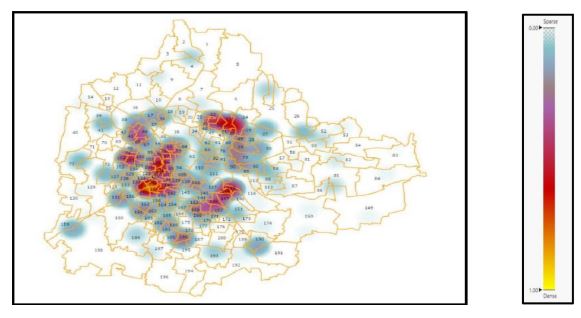

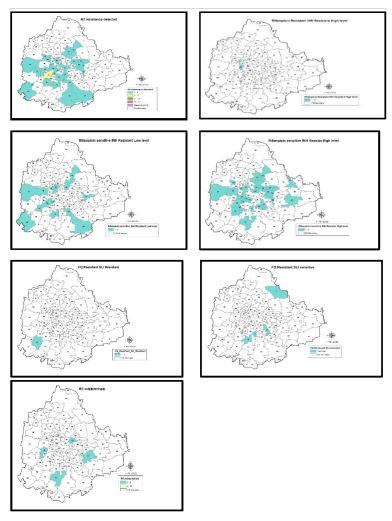

A decreasing trend in the number of registered TB cases was observed, as shown in Figure 2. This decline may be attributed to reduced reporting and registration of cases during the COVID-19 pandemic and the phases of lockdown implemented from March 2020 onward A few clusters of tuberculosis-positive cases were identified on the ward map of BBMP. Dense clustering of cases was observed in wards 134, 136, 157, and 141 (Figure 3).

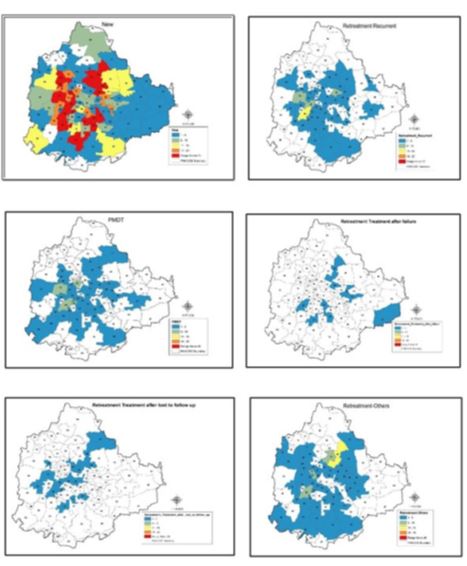

Among the 1,498 cases, the majority were newly diagnosed, accounting for 73.2% (1,096), including 79.8% (657) of males and 73.2% (439) of females.

PMDT (Programmatic Management of Drug-resistant TB) cases constituted 7.7% (115), with 7.1% (67) among males and 8.7% (48) among females. Retreatment due to recurrence comprised 7.7% (116) of cases, including 9.2% (87) males and 5.3% (29) females. Retreatment following treatment failure accounted for only 0.7% (10), all of whom were males (1.1%), with no cases reported among females. Retreatment after loss to follow-up represented 1.7% (26), including 2.5% (24) males and 0.4% (2) females. Cases requiring retreatment for other reasons accounted for 9.0% (135), comprising 10.9% (103) of males and 5.8% (32) of females.

The spatial distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis cases according to their type of case registration in the NIKSHAY portal is depicted in Figure 4. New cases were reported across all pin code areas of the BBMP, with pin codes registering more than 20 cases highlighted in red. These spatial patterns underscore the need for area-specific TB control strategies and follow-up interventions. Figure 4 also illustrates that drug-resistant and retreatment cases, while more widely dispersed, still exhibit localized hotspots, whereas new TB cases form dense clusters.

Retreatment Cases

The retreatment cases (n=287) were categorized into recurrent, treatment after failure, treatment after lost to follow-up, and other reasons. These cases were distributed across 28 pin code areas, while retreatment recurrent cases are spread across 45 geographic codes.

Drug Resistance

Among the 115 cases with drug resistance, rifampicin resistance (RIF R) was detected in 40.0% (46), comprising 26.1% (30) of males and 13.9% (16) of females. Resistance to both rifampicin and high-level isoniazid (RIF R, INH R high) was observed in 0.87% (1) of cases, with only one female affected. Rifampicin-sensitive but high-level isoniazid resistance (RIF S, INH R high) was found in 33.0% (38) cases-26.1% (21) males and 13.9% (17) females. Low-level isoniazid resistance with rifampicin sensitivity (RIF S, INH R low) accounted for 17.4% (20) of cases, including 9.57% (11) males and 7.83% (9) females. Rifampicin-indeterminate results were reported in 4.3% (5) of cases-2.58% (3) males and 1.72% (2) females. Fluoroquinolone (FQ) and second-line injectable (SLI) resistance was seen in 0.87% (1) of cases, affecting only one female, while FQ resistance with SLI sensitivity was observed in 3.5% (4) of cases-1.75% (2) males and 1.75% (2) females. Overall, males constituted 58.2% (67) and females 41.8% (48) of the drug-resistant cases.

Spatial Distribution Based on Drug Resistance

Figure 5 shows the distribution of tuberculosis cases based on the presence of drug resistance. In the GIS image of the study area, light blue colour represents the areas with 1-5 cases. Clustering of INH resistance cases was observed in several locations. Rifampicin resistance was confined to two geographical areas, one of which (code 10) also reported a case with concurrent INH resistance. Four areas (codes 5, 17, 78, 48) showed indeterminate rifampicin resistance. Fluoroquinolone resistance was seen in five areas, with concurrent SLI resistance identified in one of them. Rifampicin resistance and high-level isoniazid resistance were recorded in one location, while rifampicin-resistant cases showing INH sensitivity were found in another. Rifampicin resistance was not detected in 510 cases. The spatial distribution of cases is shown in Figure 5. The pin codes are colour-coded according to the number of cases registered.

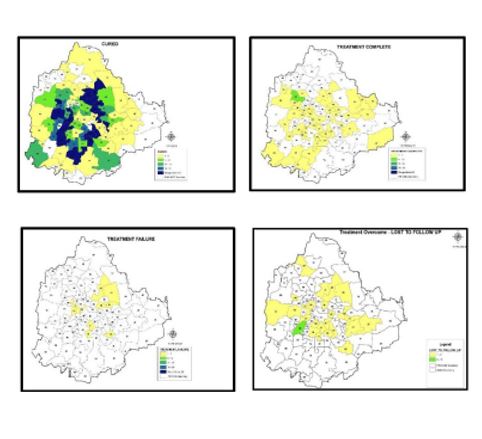

Treatment Outcome

The spatial distribution of treatment outcomes is presented in Figure 6, with areas colour-coded according to the number of cases. Ten pin code areas exhibited treatment failure cases, shown in yellow on the map. Five of these areas also reported cases of loss to follow-up. Also, all pin code areas with cases of treatment after loss to follow-up and treatment after failure occurred in areas that also had drug-resistant cases.

Discussion

The application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in health significantly impacted the healthcare delivery system. This study assessed the application of GIS technology as a tool to identify the geospatial distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis cases and to identify factors influencing such distribution. By integrating spatial data with mapping techniques, GIS enables health organizations to better understand the distribution of TB cases, identify high-risk areas, and implement targeted interventions. Overall, GIS enables a spatial perspective on TB control by helping health organizations to better understand the disease distribution, identify at-risk populations, and design targeted interventions, thus enhancing decision-making and resource allocation for TB control programs.

The pattern of tuberculosis (TB) cases can vary depending on various factors such as geographical location, population demographics, healthcare infrastructure, and reporting systems. Month-wise pattern of TB cases may follow certain trends, although these differ across regions. In general, TB cases tend to be more prevalent during colder months, possibly due to factors such as increased time spent in overcrowded, poorly ventilated indoor environments, which can enhance transmission.4 However, this can vary depending on local climate and other environmental factors. In the current study, the highest number of cases was detected in January 2020, while the lowest was reported in March 2020. However, the number of cases reported between January and May 2020 may also have been influenced by the phase-wise lockdown imposed due to COVID-19 in India. Shrinivasan R et al., reported that the number of tuberculosis cases registered as being on treatment in April 2020 fell to half of the February levels, and by June 2020, over 23,000 fewer patients had successfully completed TB therapy compared to January 2020.5 A previous study by Thorpe et al. reported that the diagnosis of TB peaked between April and June and the lowest was between October and December, with maximum variation observed in areas of North India and minimal variation in South India.6

TB is influenced by various socioeconomic factors, making it important to understand the disease patterns. The distribution of tuberculosis (TB) cases can vary across age groups, with certain groups being more affected than others. In the current study, the maximum number of cases was found in the age group of 15-25 years, followed by 46-55 years, while the least number of cases was reported in the age group 0-14 years, and in those above 65 years. The majority of the cases were males, accounting for 63% (948). However, in the age groups of 0-15 years and 15-25 years, the number of cases reported among females was higher compared to males. A study by Fazaludeen Koya S et al. reported that male TB patients had a higher prevalence of diabetes than female patients, except in western India and rural India. In western India, the prevalence of diabetes was higher among female pulmonary TB patients, whereas in the rural areas, diabetes prevalence was nearly gender independent.7 Another study conducted by Rao S et al. found that the male-to-female ratio among pulmonary tuberculosis patients was 2:1.8 Dhamnetiya D et al. reported that the incidence rate of tuberculosis among females showed a substantial increase in the 5 to 24 year age group, followed by a decline in all the subsequent ages.9 The distribution of TB cases according to age and sex can vary depending on the epidemiological context as well as the health-seeking behaviour of the population.

Diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis are conditions that can interact and influence the management and outcomes of both diseases. In the current study, the majority of tuberculosis cases (94.5%, 1416) were non-diabetic, while 5.5% (82) were diabetic. Diabetes mellitus was more common among males (48) compared to females (34). A study conducted by Fazaludeen Koya S et al., reported that the prevalence of diabetes amongst TB patients in India ranges between 12.39% and 44%, with the highest prevalence in southern states, followed by the northern states. Kerala reported the highest prevalence (44%), while Madhya Pradesh reported the lowest (12.39%). Independent studies conducted in various Indian states (north, south, central, east, and western India) similarly found that older pulmonary TB patients (> 50 years), those who are overweight or obese, and individuals who consume alcohol or smoke have significantly higher odds of having diabetes compared to younger patients (< 40 years). These studies also noted that pulmonary TB patients with diabetes tend to have lower cure rates and poorer treatment outcomes than those without diabetes.7

For appropriate treatment and management, tuberculosis cases are categorized as new or retreatment cases. In the current study, 73.2% (1096) of the cases were new. Other categories included PMDT cases (7.7%, 115), retreatment due to recurrence (7.7%, 116), retreatment after treatment failure (0.7%, 10), retreatment after loss to follow-up (1.7%, 26), and other retreatment categories (9%, 135).

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that globally, 3.5% of new TB cases and 18% of previously treated cases exhibit multidrug-resistant or rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB). Drug resistance in tuberculosis is a major concern, posing significant challenges to TB control and treatment initiatives. According to the first National Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance survey conducted by the Indian Government in collaboration with WHO and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), nearly 23% of new cases exhibited resistance to at least one drug, with MDR-TB detected in 3% of cases.10 A 2017 study estimated that India had approximately 65,000 MDR/ RR-TB patients, with a prevalence of 2.8% among new TB cases and 12% among previously treated TB cases. Similar to global trends, there remains a substantial gap in the detection and treatment of MDR/RR-TB patients in India.11

In the current study, around 48.9% (33 cases) did not show any drug resistance. Among the drug-resistant cases, resistance to rifampicin and/or isoniazid was common. Drug resistance surveillance data from three states of India reported MDR-TB prevalence among new cases as 2.4% in Gujarat (2007–2008), 2.7% in Maharashtra (2008), and 1.8% in Andhra Pradesh (2009).12 Independent risk factors for MDR-TB include age ≤ 60 years, male gender, overcrowding, previous TB treatment, and prior contact with an MDR patient.5 Several studies on geospatial patterns of MDR-TB have shown that MDR-TB cases tend to cluster within certain geographical areas, highlighting the importance of intensified control activities in such areas.13-15 If drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) is characterized by areas of concentrated risk rather than uniform spatial distribution, targeted control efforts in these high risk areas may be more effective than adopting a blanket approach for disease control.

Assessment of treatment outcomes is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of TB control programs, identifying areas for improvement, and ensuring appropriate management of patients. The current study categorized treatment outcomes as cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, and lost to follow-up. The results indicate that cases of treatment after loss to follow-up and treatment after failure were predominantly clustered in areas with reported drug-resistant cases.

In summary, the application of GIS technology to map the geospatial distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis cases can provide valuable insights into disease patterns, determinants, and potential intervention strategies. By combining spatial analysis with socioeconomic and environmental data, along with visualization techniques, GIS can aid in effective decision-making, resource allocation, and surveillance efforts, ultimately contributing to improved TB control and prevention strategies.

Limitations

This study has few limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts the ability to conclude causality, as data were captured at a single point of time. The use of postal PIN codes may not offer accurate spatial resolution when used for geolocation, particularly in densely populated or overlapping areas. Additionally, behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic factors influencing the distribution of tuberculosis were not investigated.

Conclusion

The current study reveals distinct patterns in the notification of TB cases, case types, drug resistance patterns, and treatment practices across the pin-code areas of BBMP, Bengaluru. It underscores the value of geographic information tools as an important addition to existing strategies for TB management in India.

Acknowledgment

Nil

Conflicts/Funding

There is no conflict of interest

Supporting File

References

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2023 [cited 2024 Apr]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact sheets/ detail/tuberculosis#:~:text=Key%20facts,with%20 tuberculosis%20(TB)%20worldwide.

2. Lönnroth K, Raviglione M. The WHO’s new End TB Strategy in the post-2015 era of the Sustainable Development Goals. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2016;110(3):148-50.

3. Geographic Information System (GIS). Open Educational Resource [Internet]. Available from URL: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/ resource/geographic-information-system-gis/

4. Ríos M, García JM, Sánchez JA, et al. A statistical analysis of the seasonality in pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Epidemiol 2000;16(5):483-488.

5. Shrinivasan R, Rane S, Pai M. India’s syndemic of tuberculosis and COVID-19. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5(11):e003979.

6. Thorpe LE, Frieden TR, Laserson KF, et al. Seasonality of tuberculosis in India: is it real and what does it tell us? Lancet 2004;364(9445):1613- 1614.

7. Fazaludeen Koya S, Lordson J, Khan S, et al. Tuberculosis and diabetes in India: Stakeholder perspectives on health system challenges and opportunities for integrated care. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2022;12(1):104-112.

8. Rao S. Tuberculosis and patient gender: An analysis and its implications in tuberculosis control. Lung India 2009;26(2):46-7.

9. Dhamnetiya D, Patel P, Jha RP, et al. Trends in incidence and mortality of tuberculosis in India over past three decades: a joinpoint and age-period-cohort analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2021;21(1):375.

10. National TB Elimination Programme. Guidelines for programmatic management of drug resistant tuberculosis in India. 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun]. Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php? zlid=3315

11. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017 [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2017 [cited 2024 Jun]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/ publications/global_report/MainText_13Nov2017. pdf?ua=1

12. Institute of Medicine (US). Facing the reality of drug-resistant tuberculosis in India: Challenges and potential solutions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012. Chapter 2, Drug-Resistant TB in India. [cited 2024 Jul]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100386/

13. Manjourides J, Lin HH, Shin S, et al. Identifying multidrug resistant tuberculosis transmission hotspots using routinely collected data. Tuberculosis 2012;92(3):273-279.

14. Theron G, Jenkins HE, Cobelens F, et al. Data for action: collection and use of local data to end tuberculosis. Lancet 2015;386(10010):2324-2333.

15. Alene KA, Viney K, McBryde ES, et al. Spatial patterns of multidrug resistant tuberculosis and relationships to socioeconomic, demographic and household factors in northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2017;12(2):1-14.