RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Muralidharan A R, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, BGS Medical College & Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Community Medicine, BGS Medical College & Hospital, Adichunchanagiri University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

3Department of Community Medicine, BGS Medical College & Hospital, Adichunchanagiri University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4Department of Community Medicine, MMCRI Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding Author:

Muralidharan A R, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, BGS Medical College & Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India., Email: drmuralistat75@gmail.com

Abstract

Transit walks are structured observational tools employed in community medicine to evaluate environmental, health, and social conditions within a community. These walks offer critical insights into local determinants of health, facilitate community engagement, and help guide targeted public health interventions. This study outlines the objectives, methodology, applications, and challenges of transit walks, emphasizing their role in community health assessment. The key objectives include assessing health needs, evaluating environmental conditions, mapping healthcare resources, understanding social determinants, and promoting community participation. A systematic approach was used, beginning with defining the objectives and forming a multidisciplinary team. Transit walks involved sector-wise community coverage, structured observation using a standardized checklist, and interaction with residents to gather qualitative data. Observations were analyzed alongside existing health records to identify public health priorities and inform intervention strategies. Transit walks are practical, community-engaged methods for identifying public health issues and informing responsive interventions. Their structured and participatory nature makes them indispensable in community-based health assessment. Future work should focus on standardizing methodologies and addressing implementation barriers to enhance their utility.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

A transit walk is a structured observational method used in community medicine to assess environmental, health, and social conditions within a community. This systematic walk-through helps medical professionals, public health workers, and researchers understand the challenges faced by the population, enabling them to develop targeted interventions. The approach aligns with community-based participatory research (CBPR), which emphasizes direct community engagement to improve health outcomes.1

Objectives of a Transit Walk

The primary objectives of a transit walk include:

1. Assess Community Health Needs

Identifying prevalent health conditions, sanitation issues, and risk factors influencing morbidity and mortality is crucial for targeted interventions. Studies suggest that community-based assessments help detect disease trends and guide resource allocation.2

2. Evaluate Environmental Conditions

Observing air quality, water sources, waste disposal, and hygiene practices helps determine environmental risk factors. According to Prüss-Ustün et al., approximately 23% of global deaths are linked to environmental hazards, highlighting the importance of environmental assessments in public health.3

3. Identify Healthcare Resources

Mapping hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, and traditional healthcare providers improves access to healthcare services. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) emphasizes that proximity to healthcare facilities directly impacts disease prevention and management.4

4. Understand Social Determinants of Health

Assessing socio-economic factors, education levels, employment status, and living conditions helps identify healthcare disparities. Marmot et al. stress that social determinants play a major role in health inequities and should be a core focus in public health initiatives.5

5. Engage with the Community

Interacting with residents to understand their perceptions of health and healthcare access fosters trust and enhances participation in health programs. Community engagement has been shown to improve the effectiveness of interventions.

Methods

Preparation

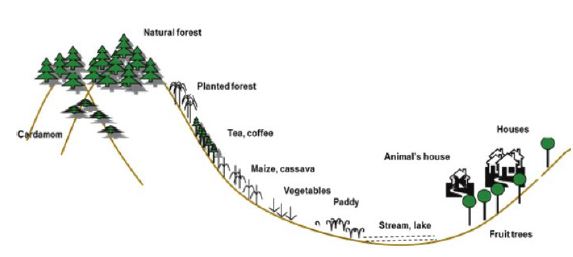

Define objectives and parameters of the transit walk based on epidemiological data. Form a multidisciplinary team (doctors, community health workers, students, etc.) to provide diverse perspectives. Gather the necessary tools, including survey forms, GPS mapping devices, and photographic documentation (if permitted). Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping has been recommended for community health assessments (eg. Figure 1).7

Implementation

Divide the community into sectors and assign groups to specific routes for systematic coverage. Observe and document key findings on health, infrastructure, and the environment. Engage with residents to gather qualitative insights into their health concerns. Identify potential risk areas such as open drains, waste accumulation sites, or unhygienic markets.

Analysis and Reporting

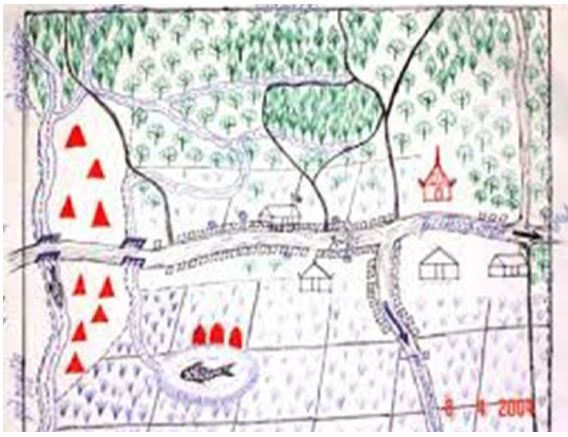

Compile and analyze observations, integrating qualitative and quantitative data. Compare findings with health records and epidemiological data to validate observations. Prepare a comprehensive report with recommendations for community interventions that align with public health frameworks.8 Table 1 presents the checklist for a transit walk, and Figure 2 demonstrates the source map.

Applications in Community Medicine

1. Disease Surveillance

Observational studies conducted during transit walks help detect disease outbreaks and emerging health threats. Surveillance techniques combined with community engagement have been successful in detecting infectious diseases early.9

2. Urban and Rural Health Planning

Findings from transit walks inform policies on sanitation, waste management, and healthcare accessibility, thereby improving urban and rural health planning. Studies indicate that urban planning significantly impacts community health.10

3.Health Promotion Programs

Targeted interventions for malnutrition, maternal health, or vaccination programs based on transit walk data improve public health outcomes. Research suggests that culturally tailored interventions enhance program success rates.11

4. Environmental Health Assessment

Monitoring pollution levels and water quality helps understand disease causation and environmental health risks. The WHO reports that improving environmental health can prevent millions of deaths annually.12

Challenges and Considerations

1. Community Resistance

Some residents may be hesitant to share information due to distrust or privacy concerns. Building community trust is essential, as outlined in CBPR methodologies.13

2. Time Constraints

A single transit walk may not capture all aspects of a community’s health, necessitating multiple observations and longitudinal studies.

3. Ethical Concerns

Respecting privacy and obtaining informed consent when engaging with residents is crucial. Ethical guidelines for community-based research should be strictly followed.14

Conclusion

A transit walk is a valuable tool in community medicine, enabling healthcare professionals to assess real-world conditions affecting health and well-being. By integrating structured observations with community engagement, targeted interventions can be developed to improve public health outcomes. Future research should focus on refining standardized methodologies for transit walks to enhance their effectiveness in diverse settings.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173-202.

2. Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT et al. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in health. Epidemiologic Reviews 2003;26(1):92-103.

3. Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Neville T, Bos R, Neira M. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: an updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017;39(3):464-475.

4. World Health Organization. Global Health Observa-tory Data Repository. 2015, Available from: https:// www.who.int/data/gho

5. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequali-ties. Lancet 2005;365(9464):1099-104.

6. O'Mara-Eves A, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health. BMC Public Health 2013;13(1), 834.

7. Higgs G, et al. The use of GIS in public health planning. Social Science & Medicine 2005;60(7): 1655-1667.

8. Green LW, Kreuter MW. (2005). Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

9. Heymann DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. American Public Health Association. 2014.

10. Rydin Y, et al. Shaping cities for health. Lancet 2012;379(9831):2079-2088.

11. Resnicow K, et al. Cultural sensitivity in public health. Annual Review of Public Health 2000;21(1), 329-347.

12. World Health Organization. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. (internet) 2018 (cited 2025 March 3). Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/ item/9789241565196.2016

13. Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:325-50.

14. Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA 2000;283(20): 2701-11.